• Lagos loses $4b yearly to flooding, third of population may be displaced

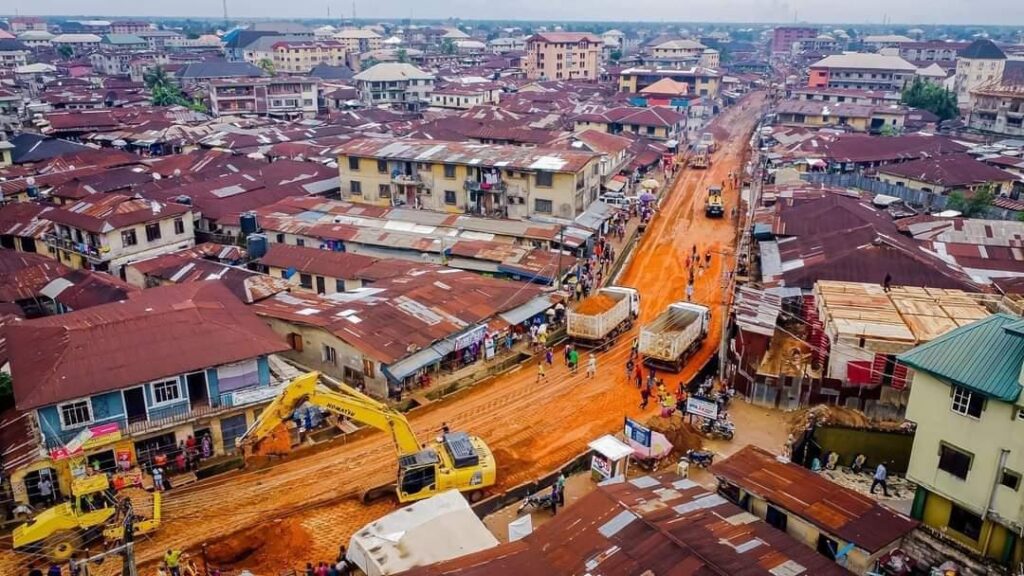

Lagos has witnessed floods submerging vehicles and houses, displacing thousands from their homes, which has been partially blamed on sand filling and illegal sand mining along the coastline. Experts warn that building on water body is a cheap solution that have costly implication, CHINEDUM UWAEGBULAM writes

With the rains yet to abate, Lagos is facing an increasing threat of severe yearly flooding and recent projections revealed rising sea levels are likely to severely impact the city by 2050, with vast swathes of land potentially rendered unlivable.

For years, communities along the coastline have fallen victim to ocean surges as a result of climate change. Hundreds of other residents have watched helplessly as tidal waves submerge their homes, especially in the Okun Alfa community, whose landscape has been consumed by the sea.

Currently, most of the coastal communities are jittery due to the fear of impending flooding and erosion, which has made the Lagos State government issue notice recently. The government advised residents of Ikoyi, Lekki, Victoria Island, and the coastal areas of Epe and Badagry to be wary of backflow due to the high tide in the Lagos lagoon.

The state government had said the high tide of the lagoon has made it difficult for storm run-off from the various channels to discharge effectively into the lagoon which may cause stagnation into the streets and major roads until the level of the lagoon subsides to allow for a discharge of the channels.

The development may reverse dividends accruing to Nigeria from its 853-kilometre coastline as a new report warns that rising seas could affect three times more people and submerge some of the world’s coastal cities resulting in shrinking land area, coastal flooding, more powerful storm surges, and the need for better mitigation.

In 2021, the global sea level set a new record of high-97 mm (3.8 inches) above 1993 levels. The rate of global sea level rise is accelerating; it has more than doubled from 0.06 inches (1.4 millimeters) per year throughout most of the twentieth century to 0.14 inches (3.6 millimeters) per year from 2006-2015.

African coastlines have experienced a steady rise in sea levels for four decades. At the current pace, sea levels are projected to rise by 0.3 meters by 2030, affecting 117 million Africans. If global warming is contained to 2˚C above 1990 levels, sea level rise may be limited to 0.4 meters.

However, a 4˚C level of global warming would lead to a one-metre rise in sea levels by the end of the century. The global sea rise is an outcome of the buildup of greenhouse gas emissions that have resulted in a 0.63˚C-increase in median ocean temperatures over the past century.

According to the latest Africa Centre for Strategic Studies report, rising sea levels are triggering coastal flooding and erosion, as well as the loss of the coastal habitats that provide natural shoreline protection from storm surges. The loss of these habitats increases the number of people at risk.

The rise in sea levels is occurring as the population of Africa’s coastal cities is skyrocketing. Between 2020 and 2030, Africa’s seven largest coastal cities- Lagos, Luanda, Dar es Salaam, Alexandria, Abidjan, Cape Town, and Casablanca – are projected to grow by 40 per cent (48 million people to 69 million) compared with the continent’s overall anticipated increase of 27 per cent (1.34 billion to 1.69 billion).

Smaller coastal cities may expand even faster: Port Harcourt, for example, is expected to grow 53 per cent over this decade. Globally, Africa’s coastal regions are anticipated to experience the highest rates of population growth and urbanisation in the world.

This demographic pressure is being driven by the economic significance of Africa’s coastal cities. Africa’s blue economy—comprising ports, fisheries, tourism, and other coastal economic activity—is conservatively projected to grow from $296 billion in 2018 to $405 billion by 2030. Coastal megacities like Lagos and Dar es Salaam power national economies.

According to the document, rising oceans are also behind the increasing incidences of “100-year floods” (having a one per cent chance of occurring in any given year). Historically rare, extreme sea level events (the combination of mean sea level, tides, and wave surges) are occurring increasingly frequently, especially in tropical regions.

Across large African river basins, the frequency is projected to increase to one in 40 years at 1.5°C and 2°C global warming, and one in 21 years at 4°C warming. Under the business-as-usual model, for some parts of coastal West and East Africa, these extreme outcomes could become yearly events.

By 2030, an estimated 108 -116 million people in Africa will live in low-elevation coastal zones – defined as areas 10 meters or less above sea level, a figure projected to double by 2060.

In the near term, West Africa will be most directly affected, comprising 85 per cent of the projected 100 million population affected on the continent, though every region is threatened. Egypt and Nigeria, both with high-density metropolises near the coast, are anticipated to face the greatest population disruptions.

The report noted that Africa’s vulnerability is exacerbated by increased coastal development. “Unfortunately, some of the more densely packed cities—such as Lagos, Dakar, and Alexandria – are victims of poor coastal planning. The World Bank estimates this erosion, flooding, and pollution inflict $3.8 billion in damage to these countries yearly. Many coastal residents will be forced to relocate.

Lagos, according to the report, a low-lying city on Nigeria’s Atlantic coast, also experiences the triple impact of perennial fluvial (river), pluvial (rainfall), and coastal flooding. Adding up the damages to assets, economic production, and mortality, the World Bank found the total cost of fluvial and pluvial flooding in Lagos is $4 billion yearly.

The Guardian gathered that rising sea levels, combined with high urbanisation, will exacerbate future damage. By some estimates, at the 3°C global warming scenario, a third of Lagos’s population will be displaced by the sea.

Home to more than 24 million people, Lagos witnesses floods submerging vehicles and houses, displacing thousands from their homes, which has been partially blamed on sand filling and illegal sand mining along the coastline.

Startling findings from a new UN data platform released recently revealed that the marine dredging industry is extracting a staggering six billion tonnes of sand and sediment yearly. This is equivalent to over one million dump trucks every day – placing immense pressure on marine biodiversity and the well-being of coastal communities.

While shallow sea mining for sand and gravel is vital for various construction projects, they pose a major threat to coastal communities facing rising sea levels and storms.

Sand extraction also endangers coastal and seabed ecosystems, impacting marine biodiversity, nutrients from the sea and noise pollution, as well as impacting aquifer salinisation and future tourism development, according to the UN agency’s 2022 Sand and Sustainability report.

Former Director-General, Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF), Dr Muhtari Aminu-Kano, said Lagos and other coastal cities globally that are less than one metre above sea level could be submerged by 2050 if the surge continues.

“The projection by scientists in the United Nations, who are the authority on climate change effects, after extensive studies, says there is the likelihood of the world’s ocean rising by one meter between 2030 and 2050.

“Hence, any city less than one metre above sea level is under threat and Lagos is part of the many others,’’ he noted that part of the reasons for ocean encroachments and beach erosions was the activities around the coastlines.

He stated: “It is a danger caused by climate change and we have got to take it seriously and apply steady and serious measures beyond infrastructure projects to deal with it.

“Sea level rise is another looming danger that could come to threaten the existence of Lagos if we do not treat it with seriousness. This is not a problem for Lagos alone to carry; it is a national problem that should involve the Federal Government.”

The Director, Health of Mother Earth Foundation (HOMEF), Dr Nnimmo Bassey said: “Land reclamation is a reckless denial of the reality of climate change and so it going to compound the problem. It is against actions that nations are carrying out to solve climate change and there is nothing smart about it. We are reducing the chance of people to have sufficient food especially proteins from marine resources. It is the wrong time to think of expanding communities into the sea rather, we should be moving to higher ground.”

“We are having sea level rise, more flood and so we need more wetlands and territory to soak up the floods and to dry our cities. Sand filling destroys marine ecosystems and so we should be more concerned about how to live with nature, more efficient in the utilisation of lands that are already developed. We should be looking at how to reclaim open spaces, we need more spaces in our cities, and we don’t need more concrete and asphalt.”

He also stated that it is time for authorities to realise the precarious nature of Nigeria’s coastline, which is a very low line, and a lot of coastlines are sinking lands. Bassey said anybody who looks to the cities or the lagoon or whatever water body to build is taking a cheap solution that would have a costly implication.