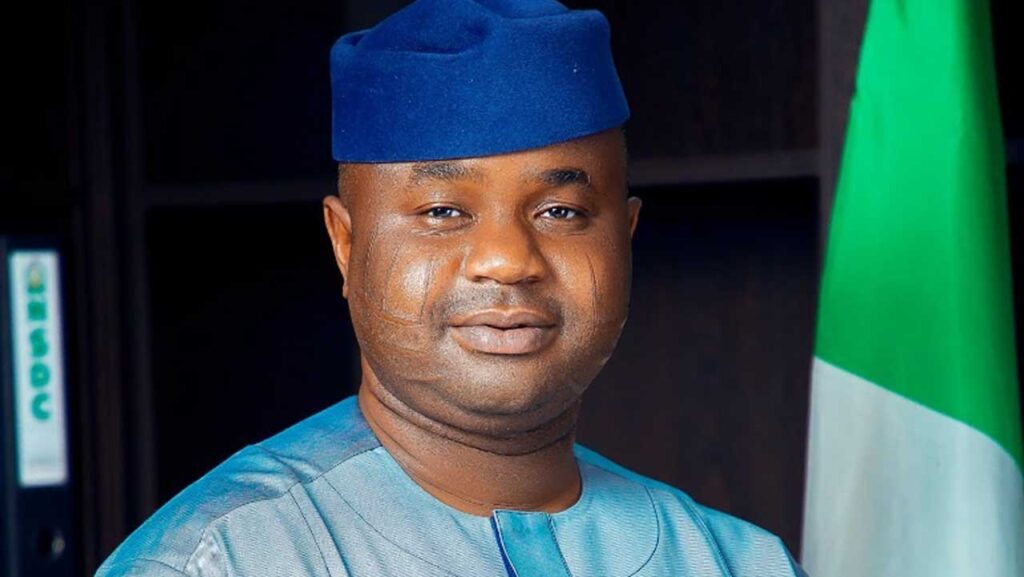

PHOTO: www.bbc.co.uk

As I have articulated elsewhere, “state-bearing nation refers to the strategic control of state institutions by a nationality, not necessary dominant demographically in a plural society, but capable of dictating the content and direction of state policies” (See The Nigerian Troubadour: Statehood or Nationhood? Ekpoma Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 6, no. 3, Nov. 2019).

In his explanation of the ‘Lugardian Architecture’, Ofeimun notes its predictability, that is, “ ‘A culture of turf-control’ and ‘turf-defence’ has been evolved which thrives on the capacity to extract largesse from the South while retaining as much as possible of what is considered Northern. It so happens that what is considered Northern is not commonly shared by Northerners—whether this is viewed in terms of a common culture, religion, economic resources or political power. But it is the necessity to achieve extractions from the South that aids a common perception of the need to unionize to maintain the veto built into the colonial mandate. Unionization, which is what the concept of Arewa actually represents, is then defended along lines that require specific strategies to reduce Southern capacity for resistance to Northern domination” (See The National Question: From a ‘mere geographical expression’ to a cultural expression in Constitutionalism and National Question, Centre for Constitutionalism and Demilitarisation, 2000, pp. 69-85).

The social construction of the ‘Lugardian Architecture’, the subject of our discussion, dates back to the decolonisation process. If we adopt Kunle Lawal’s periodisation, it is about 1945-60. In the decolonisation process in Nigeria, available archival records revealed that both the British and the United States shared intelligence on who would become leaders in an independent Nigeria; and how the country could be secured as an extension of Britain and Western powers free from the Soviet’s and Nasserite’s influences (Olakunle, 1997). According to Lawal, “While there was no direct or covert support for other nationalists during the decolonisation era in Nigeria, records of dispatches by the U.S. embassy in Lagos to the Department of State seem to suggest that they were not necessarily indifferent to the question of who was to lead the emergent country at independence. Like the British, the American diplomats in Lagos seem to have concluded that the Northern region held the key to an emergent Nigerian nation. In fact, the northern factor was the most important factor in the attitude of the United States to personalities and politics in Nigeria in the 1950s”.

Subsequent events became path-dependent on account of the decision to hand over control of independent Nigeria to the North. One major event is the head count that resulted in a false population census to decide electoral outcome since democracy was somewhat a game of numbers. Another is the manipulation of the election results, and the two variables were part and parcel of process-rigging of the electoral process.

Babatunde Ahonsi and Kole Omotoso, in their works have provided instantiation of these claims. In his 1988 essay in African Affairs, Ahonsi argued that the census in post-colonial Nigeria did not reflect heinous inflation and that claims of distortion are a function of intense ethnic struggle over control of natural resources. However, he noted that the thirteen attempts made between 1966-1973 were not successful, and that all colonial censuses were technically deficient.

Omotoso’s Just Before dawn, a faction of sorts, also adverted to this controversy. He notes that “the representatives of the emirate at the constitutional talks had insisted on 50 per cent representation in the new House of Representatives in Lagos. A. T Weatherhead, a district officer in the North during the population census of 1952 had instructions to the effect that, ‘the claim that well over half of the population of Nigeria is in the Northern Region had to be established both for the purposes of representation and for capitation share of taxes.’ None of the politicians from the Southern Regions could call their bluff.

The regional boundaries had been settled decades earlier in favour of the Northern Region. The population figures had also been worked to reflect the political arrangement of the British: to the North numerical advantage was the sole defence against political and economic domination by the more advanced South, and without this defence, nothing would have persuaded them to become partners in an independent Nigeria” (see Just Before Dawn, Chapter 7, The Frantic Fifties, for details).

Harold Smith, an Oxford graduate, and a British colonial officer, who worked in the Ministry of Labour, Lagos, in the 1950s claimed that the British tampered with the elections during the decolonisation process in Nigeria. In a July 30th, 2007, BBC Channel 4 documentary, titled “The Gift of Democracy” anchored by Mike Thompson, Smith averred that: “In 1956, I was in Lagos on the staff of the Ministry of Labour when I received the secret file which had a minute which ordered me to get involved in the regional elections which were taking place. It told me to take all the vehicles of the Ministry of Labour, all staff, the clerical staff, and as many senior staff as I could find to act on behalf of the minister. The chap was Festus Okotie-Eboh, to carry out the minister’s, the reporting minister’s instruction, and get his party colleagues elected.” He justified the claim “… because the plan was to put the North in government, in power. The elections were just to be fixed”. And in respect of the 1959 general elections, Thompson flipped the thoughts of the Governor-General, James Robertson, contained in his memoir where he admitted inviting Abubakar Tafawa Balewa to form a government before the results of the elections were known.

At independence, the North took over political power in a coalition of the Northern Peoples’ Congress (NPC) and the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC) with Alhaji Tafawa Balewa as Prime Minister. The 1960 Constitution that ushered Nigeria into independence had engrossed what one might call autonomous political space for the various regions. In terms of policy determination, they had aligned with the expectation of the Americans for a political leadership that would draw on its strength and balance political power based on cooperation, compromise, and pragmatism in domestic and external relations (See Lawal, 1988, p. 65).

This reflection on ‘Lugardian Architecture’ will be continued next week.

• Akhaine, PhD (London), is Professor of Political Science, Department of Political Science, Lagos State University, Ojo Campus, Lagos.