Sexual violence is an age long crime that has been in existence since early civilised societies. At different times, and in different places in history, cases of sexual violence have been recorded. It is, in fact, one social problem or vice that has tormented children, young girls, women and even adult women. On a regular basis, cases of sexual violence are reported, as both young and old are raped: an indication that no one is free from the clutches of rapists.

From Lagos to Abuja, Port Harcourt to Ibadan concerns over rape have captured public attention across the country and fueled momentum to further criminalise violence against women.

One victim, Vera Uwaila Omosuwa, a 22-year-old microbiology student, was raped and brutally assaulted in 2020 in a church near her home in Benin, Edo State, and died a couple of days later from her injuries.

Hamira, a five-year-old, was also drugged and raped by her neighbour in April 2020. Her injuries were so bad she could no longer control her bladder.

Barakat Bello, an 18-year-old student, was raped during a robbery in her home in Ibadan, Oyo state. She was butchered with machetes by her rapists and died on June 1, 2020. Favour Okechukwu, an 11-year-old girl, was also gang-raped to death in Ejigbo, Lagos State.

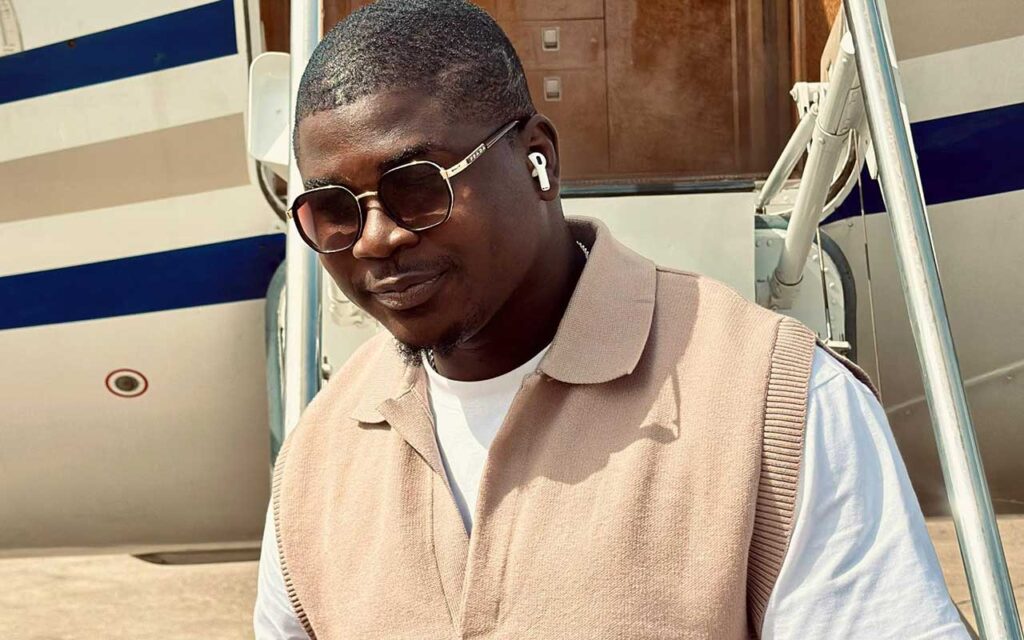

On October 24, 2023, the Lagos Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Court in Ikeja convicted Femi Olaleye and sentenced him to life imprisonment for defilement and sexual assault by penetration of his wife’s niece.

The judge, Justice Rahman Oshodi, maintained that the evidence was compelling and proven beyond reasonable doubt. Olaleye was an Optical Cancer Care Foundation doctor who was found guilty of assaulting his wife’s teenage niece for over a year between December 2019 and July 2022.

The victim reported to her aunt, Olaleye’s wife, who reported the case to the police. He was arraigned in November 2022 on two counts. The victim, Olaleye’s wife, a child-care expert, and police officers testified against Olaleye in court. According to their testimonies, he constantly assaulted the girl and even forced her to watch pornography.

Contributing to this discussion, Lois Otse Adams, in Stigma, concludes that identifying the early signs (red flags) and taking a proactive rather than a reactive step will help in minimising the incessant cases of sexual violence.

Set in Urumorh community, the book draws you into a fictive territory with zest and finesse. The Umada family is the eye of the camera through which the author examines problem of sexual violence.

In six chapters, the author uses simple English, visual illustrations and other metaphoric languages to convey her message. In the breezy fictional narrative, she ensures that the reader is not lost at any giving point.

Eddying back and front in almost two decades, the novel radiates vitality that the village is initially known for. In Stigma, the author explains that the privileging of cultures has been supplanted and deployed as an instrument to conquer, exploit and oppress the feminine gender.

Historically, the young girls in Umurohr are prone to sexual molestations because of the community’s porous border with neighbouring villages, creating gateway and link to sexual predators. Urumorh maidens suffer a series of attacks owing to engagement with these communities.

Most nights, while the female dance groups participate in dancing competitions, suitors throng the community to ask for the maidens hand in marriage until momentary loss of sanity and discipline. While some others use such opportunity to molest the young girls, however, the elders who believe in the potency of Yini, the village deity, look the other way.

From Eselikoghene, several years dance champion, who is married off as the 14th wife of an old man, in the hope that she is going to give him a male child, to Ona, the same fate of molestation befalls the young girls who end up becoming pregnant.

The miscreants perpetrate heinous crime and are left to go scot free in the name of tradition and culture because of the shame and embarrassment such act will cause the community. This trend continues until the family of Umada returns home after a sojourn in the city.

Dedicated to young girls whose voices have been silenced by the same society that is supposed to provide them safety from the marauding beasts who until a family from Urumorh Village returned home to end the societal and cultural tragedy that the village suffers.

Strictly adopting supervision mechanisms and screening measures for information, the Umada family standardises the process of information dissemination, and controls the false narrative, which has thrived in the community. The family, through the only daughter, ensures that people like Sali, Minu, and Neru did not get away with their evil. Same for Minu.

The fiction represents the author’s willingness to share the pain suffered by victims of sexual violence and molestation while reminiscing on society’s attitude towards gender based violence.

The story aims to educate families of victims of sexual molestation, abuse and rape not to keep quiet for fear of stigma. The didactic and instructional piece is a good read and suggested for both children and adult to survive predators and rapist looming large in the society.