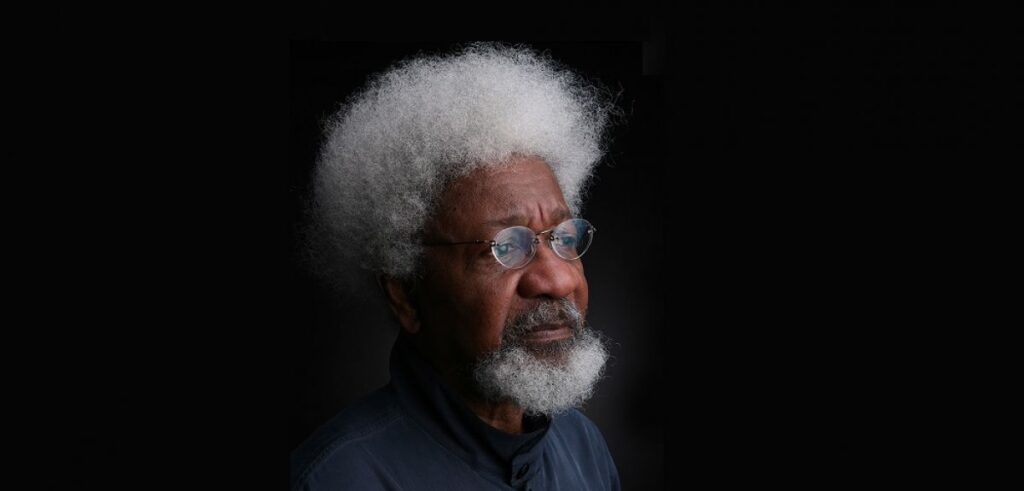

I am convinced that Nigeria would have been a more highly developed country without the oil. I wished we’d never smelled the fumes of petroleum. – Professor Wole Soyinka

I am convinced that Nigeria would have been a more highly developed country without the oil. I wished we’d never smelled the fumes of petroleum. – Professor Wole Soyinka

THE late Nigerian virtuoso, Sunny Okosun in his song Which Way Nigeria asked the then burning question: “How long shall we be patient before we reach the Promised Land?” That question is as pertinent today as it was in the 1980s when the musician posed the challenge, only that the question has taken on wider ramifications today in view of our more dynamic and broader circumstances as a nation.

To enquire about how much longer it would take to reach a promised destination presupposes that one is on course towards that destination and the corollary of this is that the destination is in sight or at least that the odds favour an end to a tortuous journey, however, long it takes to reach that end.

To be on a journey’s course equally implies that some grounds have been covered or that some territories have been conquered. The enquiry might be different from that of the maestro indicated in the foregoing if no path has been charted or if having charted a path, the path has become eroded or obscured by any circumstance, leading the traveller either to square one or to the middle of nowhere. This state of affairs is aptly expressed in the following excerpt from the poem Songs of Sorrow by the late African lyricist, Kofi Awoonor: Dzogbese Lisa has treated me thus. It has led me among the sharps of the forest. Returning is not possible. And going forward is a great difficulty (emphasis mine).

For Awoonor, the seeming despondence stemmed from a certain fait accompli which appeared to have been foisted by a celestial force over which there was no control. This is understandable, for what can a man do when he can do nothing? But when a problem is self-inflicted, then some soul-searching is required in order not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

There is no question that today everything appears to be at sixes and sevens in Nigeria with fear and uncertainty about the state of the economy and the future palpable – hanging ugly and heavy in the air. Whatever frills and thrills might have been occasioned by the emergence of Muhammadu Buhari as the President, the same appears to be dampened by an uncertain economic climate, compounded by a turbulent political ambience – no thanks to the ruling All Progressives Congress – and an unabated spate of terror attacks.

Nigeria is not alone in the excruciating economic times: It is a global wave of economic downturn occasioned by declining oil prices – the outcome of muscle-flexing by ideological oil blocs who have shown no signs of backing down on their stance. However, what makes our case at once depressing and regrettable is that we had all the time to prepare for the present times but we chose rather to play the ostrich.

Today, Nigeria stands on the precipice of an economic crisis and may topple over unless urgent steps are taken.

Nigeria enjoyed a colossal boom in oil prices from 1999. Oil prices rose from $10 per barrel in 1999 to $140 per barrel in 2008. So massive were the prospects of oil revenues that the Federal Government under President Olusegun Obasanjo established the Excess Crude Account (ECA) in 2004. The ECA was aimed at saving oil revenues above a base amount derived from a defined benchmark price. The objective was chiefly to protect planned budgets against shortfalls due to the potential volatility of crude oil prices. The ECA was proposed to be unlinked with government expenditures and therefore protect the Nigerian economy from external shocks.

Increasing oil prices led to the ECA increasing almost four-fold, from $5.1 billion in 2005 to over $20 billion by November 2008, accounting for more than one-third of Nigeria’s external reserves at that time. By June 2010, the account had fallen to less than $4 billion due to budget deficits at all levels of government in Nigeria and the steep drop in oil prices. However, oil prices rebounded and as of June 2014, oil prices remained above $100. But from June 2014, oil prices have fallen by more than 30 per cent to an average of about $60 per barrel and some experts have predicted that it is unlikely that the prices have reached their bottom.

Among a variety of other things, a broad range of government expenditures are associated with petroleum and in the absence of the sustainability of this critical lubricant of government and economic expenditure, the situation may be very dire.

Our subsistence hasn’t always been from the ‘black gold’, the prospects of which have now become so chaotic and uncertain that it evokes a description in John Pepper Clark’s poem Ibadan: Running splash of rust and gold – flung and scattered among seven hills like broken china in the sun. Like a spoilt child, once we happened upon this nature’s rich resource, we threw to the winds the other diverse resources which thitherto defined our economic identity. What more, we refused to heed all counsel that a mono-product economy was an accident waiting to happen.

Now that oil which is the cash cow of the Nigerian economy does not seem to ‘make sense’ anymore, the government has become frantic; government agencies have become aggressive in alternative revenue generation – more aggressive than Nigeria’s most ambitious banks are in deposit mobilisation. In just a few months of near-steady decline in oil prices, the government is somewhere between broke and apprehensive.

On the condition of the various states of the nation, the newspapers are awash with various disturbing statistics: “22 state governors owing workers salaries” – The Nation of December 25, 2014; “11 states have not paid December salaries – NLC – The Punch of December 31, 2014; “18 states bankrupt, can’t pay workers’ salaries” – Vanguard of June 15, 2015.

The statistics represent a worrisome situation: we have mostly hand-to-mouth states which know nothing of self-sustenance or internally generated revenue but which forever look unto the Federal Government for sustenance like the post-apocalyptic survivors in the adventure film Mad Max: Fury Road.

We have fared very poorly as a people. We could have avoided getting to this point of desperation if we had taken a cue from other oil producing countries, a good example being Norway, the world’s ninth largest oil exporter and the world’s fourth richest country by gross domestic product.

Norway has a diverse economy with a thriving private sector and is reputed for its effective social safety endeavors. Norway witnessed oil boom but refused to be caught by the “oil curse” or the “Dutch Disease.”

To be continued.

Opatewa, oil and gas attorney, lives in Victoria Island, Lagos.

Tel: 08039651217; pojopeter@yahoo.com