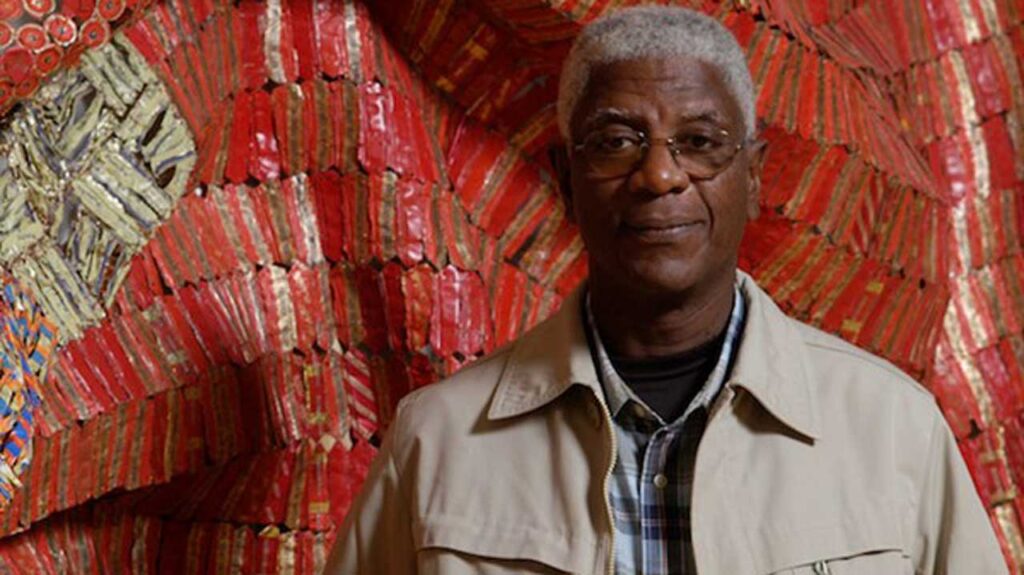

It has taken many years to find artists who can occupy a prominent place on global circuit while choosing to reside outside the metropolitan centres. William Kentridge has made his reputation from Johannesburg, El Anatsui conquered the planet while living and working in the Nigerian university town of Nsukka.

Anatsui and his contemporaries at Nsukka, including world-renowned artists, writers, poets, and dramaturges, were motivated by a sense of worldliness that was more imaginative than locational, with an abiding belief that their work could contribute to enlarging the scope of artmaking in a much-expanded, global contemporary art scene.

He told The Guardian, “when I came to Nsukka, I found the place welcoming and I didn’t think of going to another university. It was the time that I came that we had the likes of Uche Okeke, Obiora Udechukwu, Chike Aniakor, and so many artists around. Nsukka art school had a very prestigious formation. I needed a place that was very exciting.”

He added, “an artist survives very well in an environment where there is idea stimulation and I have a lot of stimulation in the environment from the things that are cultural and even the language. The Nsukka environment was exalting, people were experimenting, and sometimes, not experimenting but very active – one that urged you on to do something. It was a synergetic kind of, at that time.”

Anatsui said, “when I create work, it is in my view a metaphor reflecting an alternative response; to examine possibilities and extend the boundaries in art. My work can represent links in the evolving narrative of memory and identity. The link between Africa, Europe, and America is very much behind my work with bottle caps. I have experimented with quite a few materials. I also work with material that has witnessed and encountered a lot of touch and human use … and these kinds of material and work have more charge than material/work that I have done with machines. Art grows out of each particular situation, and I believe that artists are better off working with whatever their environment throws up.”

According to Anatsui, “I see that in Nigeria, you haven’t lost much of your culture. The colonialists did not stay long here. In Ghana, they destroyed so many things. When I came, I saw that in this area, especially the Igbo community, a lot of the culture was still intact.”

By the way, Anatsui is one of the most gifted sculptors in the world. His works are found in virtually every international art gallery, museum and cultural centre across the globe; among them are his aluminum cap sculptures created from waste liquor-bottles tops that demystify the notions of conventional classification in the visual arts.

The Ghana-born Nigerian is a master of turning trash to striking art. He uses trash, elegantly called found material — milk tins, bottle caps, driftwood, iron nails, and printing plates — as well as natural elements to compose his grandiose installations.

For purists, contemporary art is trash and rhetorical nonsense. However, in the hands of many contemporary artists, trash has become graceful art. The Nigerian-born Turner prize winner, Chris Ofili, gained tabloid notoriety owing to his intricate, hedonistic paintings incorporating animal ordure.

Born in Anyako, Volta Region, Ghana, on February 4, 1944. The youngest of his father’s 32 children, Anatsui lost his mother and was raised by his uncle. He trained at the College of Art, University of Science and Technology, in Kumasi, central Ghana and a post-graduate diploma in art education from the same school, in 1969. One of his early influences was sculptor Vincent Akwete Kofi.

He taught at the Specialist Training College (now University of Education) in Winneba, Ghana, until 1975. That same year he moved to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, where he taught sculpture and basic design. After his retirement in 2011, he became an emeritus professor in 2014.

His work with sculpture and wood carving started as a hobby to keep alive the traditions he grew up with. He began teaching at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1975, and has become affiliated with the Nsukka group.

Since the late 1990s, he has experimented with liquor bottle tops, the product of a global industry built on colonial trade routes while combining African aesthetic traditions with the global history of abstraction.

In 1990, Anatsui was invited to the 44th yearly Venice Biennale show, where five contemporary African artists, where he received an honourable mention. He was among the first batch of sub-Saharan Africans ever to present at the Venice Bienniale, the grand ball of the art world.

By 2007, the Ghana-born Nigerian artist was the beau of the very same ball, having transformed the end of the Bienniale’s main hall, the Arsenale, into a corridor of disorienting light, beamed off the sort of ingenious piece that would become his calling card: a suspended sheet woven of flattened liquor bottle caps.

In 2015, the Venice Biennale awarded Anatsui the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement.

Declared a ‘global star’ by The New York Times, he is one of a few African artists, which every critic in the Western world felt compelled to make some kind of judgment.

His beautiful sculptures, which are rich with innuendo, not only about the detrimental effects of colonisation (European countries were the first to introduce, and reap handsome profits from, the sale of liquor in parts of Africa — a continent now plagued by alcoholism), but also in terms of environmental concerns such as recycling, upcycling and waste.

The Prince Claus Award winner has drawn particular international attention for his “bottle-top installations”. These installations consist of thousands of aluminum pieces sourced from alcohol recycling stations and sewn together with copper wire, which are then transformed into metallic cloth-like wall sculptures. Such materials, while seemingly stiff and sturdy are actually free and flexible, which often helps with manipulation when installing his sculptures.

Down the years, he has always “sought to not only re-invent but to change his materials and compositional techniques, which in the end create for his audiences a scintillating and often quite magical effect.”

His artistic practice exemplifies, what has been described as, “a critical search for alternative models of artmaking that in turn questions the foundation of modernist ideals of artistic autonomy and aesthetic purity.”

Anatsui, in his six decades-old career as art scholar and sculptor, has been tirelessly preoccupied with question of ‘triumph and monument’.

Along with ambitious works, their imposing physical presence and dazzling colours, he provides a comprehensive and detailed presentation of the overwhelming power, significance, and beauty of contemporary sculptural concept.

His oeuvre serves as a testament to how art that interrogates can be developed from the environment threatened by consumerism, global warming, and climate change.

Even a cursory look at his large body of work demonstrates his linkages between sculpture and painting as well as an assemblage.

He employs fragmentation as a compositional technique to infuse even the most abstract of his works with iconic power. “For instance, the laborious manual work of flattening, cutting, twisting, and crushing bottlecaps and using copper wires to suture and stitch the elements into one dazzling epic piece serves as metaphor for the constitution of human society,” said Okwui Enwezor and Okeke-Agulu, curators of Triumphant Scales in the programme note to the Haus der Kunst opening.

They continued, “Anatsui’s ideas were formed in the context of Nsukka’s creative environment marked by artistic experimentation and aesthetic research, informed by the belief that great art can be developed anywhere in the world, independent of the so-called art centers of the West.”

The show is a testament to Anatsui’s invention of a completely new and unique sculptural form and visual language with material for artmaking revealed to him by his context of production.

In the show, he interrogates ideas that are variegated and informs his practice over the years, from circular and multi-panel wood reliefs to terracotta forms, and the later metal sculptures, he engages with complex flows of history, memory, time, and how these forces shape human society.

This speaks to his enduring meditation on the impact of colonisation and postcolonial global forces on African cultures and invests his work with a profound conceptual purpose, its invocation of resilience and fragility, and its visual resplendence.

“Emeritus Professor El Anatsui has been an important factor in the visibility of the Nsukka Art Department and the University of Nigeria at large. He has worked consistently from 1975, when he came to Nsukka, till today, leading a life of dedication to work and service to humanity. It was not a surprise that he rose to become a global star in the visual arts, with innumerable exhibitions and awards around the world.

“The University of Nigeria, Nsukka is proud of this exceptional global giant and renowned academic. That he remains strong and blazing the trail in the global art space at the age of 80 is further proof of his self-discipline and God’s grace in his life.

“We gratefully thank God for Emeritus Professor El Anatsui’s new age and wish him a longer life and good health to consolidate his noble and profound legacies,” said the vice chancellor, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Prof

For Ekenechukwu Anikpe, Emeritus Professor El Anatsui’s work and influence have left an indelible mark on the art world. “His dedication to nurturing young talent and enriching Africa’s cultural legacy is truly admirable. We honour his lifetime contributions to art and culture as he approaches his ninth decade and wish him many more years to continue giving back to the community.”

Anikpe continued, “For those of us that Anatsui taught and worked with, we are extremely proud to be associated with the globally renowned artist.”

El Anatsui’s contributions to both my academic and artistic development have been immense and deeply appreciated. He taught me as an undergraduate student and also supervised my Master of Fine Arts (Sculpture) project report. He was more than a supervisor, and I lack words to express the depth and scope of his mentorship. His watchword, “What is new?” was his way of reminding his students to continually reappraise the experimental trajectory of our studio practice. Under Anatsui’s supervision, the works I produced during my MFA programme got me a grant, which led to my first overseas travel for a residency at the Royal Overseas League in London and Scotland in 2009 and 2010, respectively.”

According to Dr Eva Obodo, “Anatsui is innovative in everything he does – even in the manner he eats popcorn with peanuts, which used to be his favourite fast food in those days. He is a wonderful teacher, and his pedagogical approach embodies unequalled innovativeness parallel to the level of creativity that his studio explorations demonstrate. Perhaps, this explains the reason his students have more than one thing they would proudly say they had learnt from him while under his tutelage. Ask any of them in a hurry, “Who is El Anatsui?”, and he would quickly reply: “The father of exploration of African indigenous materials, ideas and forms” or “A teacher with exceptional skills”.”

Anatsui is an Honorary Royal Academician of Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts and holds honorary doctorates, which include that of Harvard University and the University of Cape Town, South Africa. The Emeritus Professor has also been elected into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He also holds the Igbo traditional title of ‘Ikedire’, conferred on him by the traditional ruler of Ihe-Nsukka, Enugu State.

Anatsui’s work is found in the collections of no less than 60 of the world’s major international museums in Europe, North America, Asia, Australia, the Middle East, and Africa. Major global galleries, as well as individual continental and international art collectors, have also acquired his work.

Among some of the institutions in whose collections his works can be found are The British Museum, London; The Centre Pompidou, Paris; The de Young Museum, San Francisco; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Guggenheim, Abu Dhabi; The Osaka Foundation of Culture, Japan; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Tate, London; and The Leeum Samsung Museum, Korea.

The sculptor is a recipient of some of the art world’s most prestigious prizes and honours. These include Japan’s Praemium Imperiale (2017), which is regarded as art’s Nobel Prize.